The Colombian Nobel laureate, who lived in the city from 1967-75, is to have a €12m building specialising in Latin American literature named after him

In the digital age, building a new library filled with

old-fashioned printed books seems idealistic, almost quixotic.Not so in Barcelona. The city

council is about to open a new €12m (£10m) library next month, the latest

instalment in a programme that dates back 20 years.

The library, in the working-class district of Sant Martí de

Provençals, has been named in honour of the Colombian Nobel laureate Gabriel García

Márquez.

“The plan for the new library was under way when García

Márquez died

in 2014 so it was decided to name it in his honour because he and many

other Latin American authors had a close relationship with the city,” said Neus

Castellano, its chief librarian. “It’s a nod towards the role Barcelona has

played in Latin American literature.”

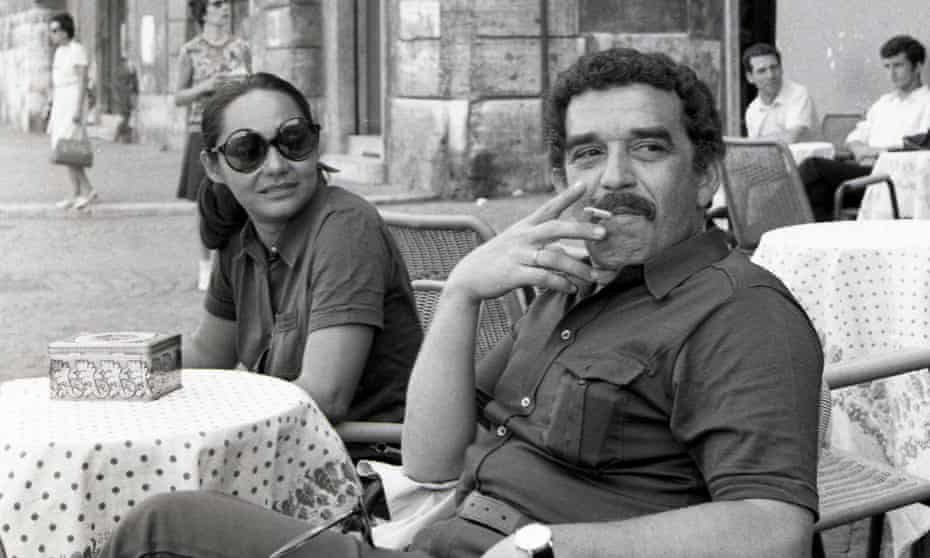

García Márquez lived in Barcelona from 1967 to 1975,

arriving shortly after the publication of his groundbreaking magical realism

novel One

Hundred Years of Solitude.

He already knew something of the city through his friend Ramón Vinyes, a Catalan writer and bookseller living in Colombia, who served as the model for “the wise Catalan” in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

However, it was the Barcelona literary agent Carmen

Balcells, one of the first to recognise the worth of the writers of the

Latin American “boom”, who persuaded Gabo – as García Márquez was

affectionately known – to move to the city.

She continued as his agent until his death, as well as representing

other luminaries of Latin American fiction such as Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas Llosa,

Carlos Fuentes and Pablo Neruda.

“They called Carmen Balcells ‘Mamá’,” Castellano said, because

she did not just help them with their writing but with finding a place to live

or schools for their children.

In his book about the period, Aquellos Años

del Boom (Those Boom Years), the journalist Xavi Ayén relates

how Balcells once asked Gabo what he wanted for his birthday. “Three thousand

dollars,” he replied. Thereafter the agent sent him $3,000 on his birthday for

the rest of his life.

Vargas Llosa, who also went on to win the Nobel prize in literature, describes disembarking in the old port, at the foot of the city’s famous La Rambla, accompanied by Julia, his wife, who was also – somewhat scandalously – his aunt, and whom he immortalised in novel Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter.

“I walked up the Rambla,” Vargas Llosa later wrote. “Excited

by the streets, clutching Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, which I’d

read on the voyage over.”

García Márquez and Vargas Llosa were briefly neighbours but

had a falling out, possibly over the latter’s second wife, during which the

Peruvian punched García Márquez in the face. García Márquez was so proud of his

black eye that he made a point of having it photographed.

García Márquez described Barcelona as “a city where I can

breathe”, and yet Spain was

then as much of a dictatorship as many of the countries he and his fellow

writers had left behind.

Ayén points out that they arrived in a Barcelona literary

world that was completely opposed to Francisco Franco’s

regime and where alternative publishers were emerging.

“It was a microclimate separated from the dictatorship,” he

said. “These writers didn’t involve themselves in the anti-Franco struggle,

with the exception of Vargas Llosa, who took part in anti-Franco

demonstrations. At the time, he and García Márquez were both on the left but

Gabo didn’t take part in demonstrations for fear that he’d be deported.”

What they were involved in was revolutionary Latin American politics, especially Cuba. Their apartments were meeting points for visitors such as Fidel Castro’s chief adviser and Che Guevara’s family.

“There were just as many reasons to censor García Márquez,

but because of his magical realism the authorities were unable to see them,”

Ayén said.

The new library that bears his name will be housed in a purpose-built

4,000 sq metre timber-framed building that has been awarded a gold LEED

certificate, the highest rating for sustainability. It will specialise in Latin

American literature and hold a collection of 40,000 relevant documents.