SOURCE: TIMES OF ISRAEL

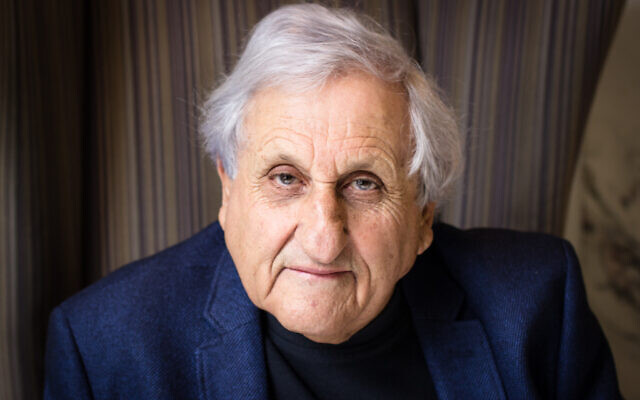

A.B. Yehoshua, a fiery humanist, towering author, and staunch advocate of Zionism as the sole answer for the Jewish condition, died Tuesday. He was 85 years old.

His wife, Ika, a psychoanalyst, died in 2016. He is survived by his three children, Sivan, Gideon, and Nahum, and seven grandchildren.

A writer, essayist, and playwright, Yehoshua was the recipient of Israel’s top cultural award, the Israel Prize, in 1995, along with dozens of other awards, including the Bialik Prize and the Jewish National Book Award, and his work was translated into 28 languages.

Eulogizing Yehoshua, President Isaac Herzog called him “one of Israel’s greatest authors in all generations, who gifted us his unforgettable works, which will continue to accompany us for generations.

“His works, which drew inspiration from our nation’s treasures, reflected us in an accurate, sharp, loving and sometimes painful mirror image. He aroused in us a mosaic of deep emotions,” Herzog added.

Prime Minister Naftali Bennett mourned Yehoshua as “one of the pillars of Israeli literature, a man whose words were read by many. He has left a crowd of readers full of admiration for the person who took a part in shaping the culture of the State of Israel. May his memory be blessed.”

Culture and Sports Minister Chili Tropper said: “Beyond his rare talent, Yehoshua was characterized by great care and sensitivity to the challenges facing Israeli society and was a social and political activist in an effort to improve society in his way. The words he wrote and the stories he told are an integral part of Hebrew literature and are in the hearts of masses of loving readers.”

Yehoshua’s work was structurally innovative and narratively traditional. There were no chapter-long sentences in his novels and no preposterous quests sapped of all plot. Instead, one was likely to meet a raw exploration of a flawed but likable protagonist, a patient, humor-laden style, and a dark storyline that deftly held the reader to the page. The sentences were long and complex, nested with meaning, and the heart of the stories could often be found in dialogue. He spoke frequently and adoringly of William Faulkner as an example of an author he admired.

Prof. Nitza Ben-Dov, herself an Israel Prize-winning scholar of literature, says that while his literary work shifted notably over the years, from surrealist stories to realist novels, he remained, above all, attuned to the society in which he lived. “He was very rooted to this place,” she said. “Practically a Canaanite.”

Several of his greatest works arguably came to define the era in which they were published. “Facing the Forests,” released in 1968, at the apex of the post-Six Day War euphoria, is to this day widely seen as the most arresting exploration of the Palestinian Nakba in Hebrew literature, signaling an awakening among his generation; and his first novel, “The Lover,” published in 1977, managed to herald the seismic shift in Israeli society with the rise of the Likud party to power and the decline of the Laborite and largely Ashkenazi left. (Yehoshua’s fiction was translated by Philip Simpson, Hillel Halkin, Nicholas de Lange, Stuart Schoffman, and others.)

Politically, on the enduring question of Palestinian statehood, his views, unlike those of many of his peers, were subject to change. After years of unbridled advocacy for a two-state solution, he broke with the tribe in 2016 and declared that the future lay in some sort of “joint endeavor.” He was not firm on the parameters of the sought-after arrangement but made clear that it would include equal rights for Palestinians.

On the matter of Judaism and the centrality of Israel, he shifted not at all. Despite howls of protest from Jewish communities abroad, he repeatedly stated that all Jews living outside the state of Israel were “partial Jews” and that even those who spent all their waking hours poring over texts and observing commandments were less Jewish than their brethren in Israel, where taxes and defense and incarceration, and all elements of daily life, are determined by Jews.

In 2006, in an essay submitted to the American Jewish Committee, he denied engaging in a “negation of the Diaspora.” Jewish communities in exile, he noted waspishly, have been around since Babylonian times, some 2,500 years ago, and will almost certainly endure for thousands of years into the future. Instead, it is Israel, home to only half of the world’s Jews, that is always perched near the precipice of extinction. Exasperated with this enduring situation, he wrote: “I have no doubt that in the future when outposts are established in outer space, there will be Jews among them who will pray ‘Next Year in Jerusalem’ while electronically orienting their space synagogue toward Jerusalem on the globe of the earth.”

In Yair Qedar’s recent documentary, “The Last Chapter of A.B. Yehoshua,” the author says that his parents’ somewhat acrimonious marriage was what cemented in him the notion that “My wife, I will love. And I will not compromise on that matter.”

He was educated at the Gymnasia Rehavia, a secular school in Jerusalem, and went on to serve in the airborne battalion of the Nahal Brigade, with which he saw action in the 1956 Suez War. But only in his final year of university, in 1959, did he first have a girlfriend. Speaking at her funeral, he said that he vividly remembered the first time he saw her, his future wife: Rivka Karni, then 19, was in uniform, standing outside a Hebrew University lecture hall, talking to a friend of Yehoshua’s, “her smile clearly seen even from the third floor.” He asked his friend, Yigal Lussin, about the soldier. “‘She’s a wonderful girl but a bit too smart for me, so I told her about you and even mentioned that you’re a promising writer,’” he recalled hearing.

Yehoshua was infatuated. He waited outside her base to meet her for a few minutes during lunch break and lingered in her dormitory in the evening. “I slowly came to realize that on account of that smile I would never finish my BA,” he said in his eulogy (Hebrew link) for her, “so I quickly proposed to her.” Within several months, the two were married. Her death, like their love, he said, developed fast.

Yehoshua was not always destined for greatness as a writer. In 11th grade, his only failing mark on his report card, the Qedar documentary revealed, was in composition. But 10 years later, he released his first collection of short stories and was promptly hailed as a writer of great insight and skill. Amos Oz, at the time still an unpublished author, wrote (Hebrew link) in a biweekly literary journal, Min Ha’Yesod, that “Yehoshua’s unique trait is expressed in his ability to create scandalous situations… and situations akin to those in a crime novel… without ever slipping into the sensationalism that lies in wait in such situations.”

Oz, later to become a friend and colleague, summed up Yehoshua’s skill as an author by saying, “While the hammer is in hand, and its weight and strength are surprising, the anvil is still too narrow.” He urged him to widen the scope of his stories.

That is precisely what followed. The title story of his 1968 collection, “Facing the Forests,” was a defining moment for many writers and readers alike. The author and poet Dorit Rabinyan described her first encounter with the text as “bewitching” and said, in a 2021 symposium at the Van Leer Institute, “that the fire in ‘Facing the Forests’ was like touching one of the elements of reality.”