SOURCE- INDIAN EXPRESS

An assistant professor in the Santali language at the

Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University in Purulia, West Bengal, Sripati Tudu started

this initiative because he wanted the document to be more accessible and

available for a wider group that may not necessarily be familiar with languages

in which a translation of the Constitution is available.

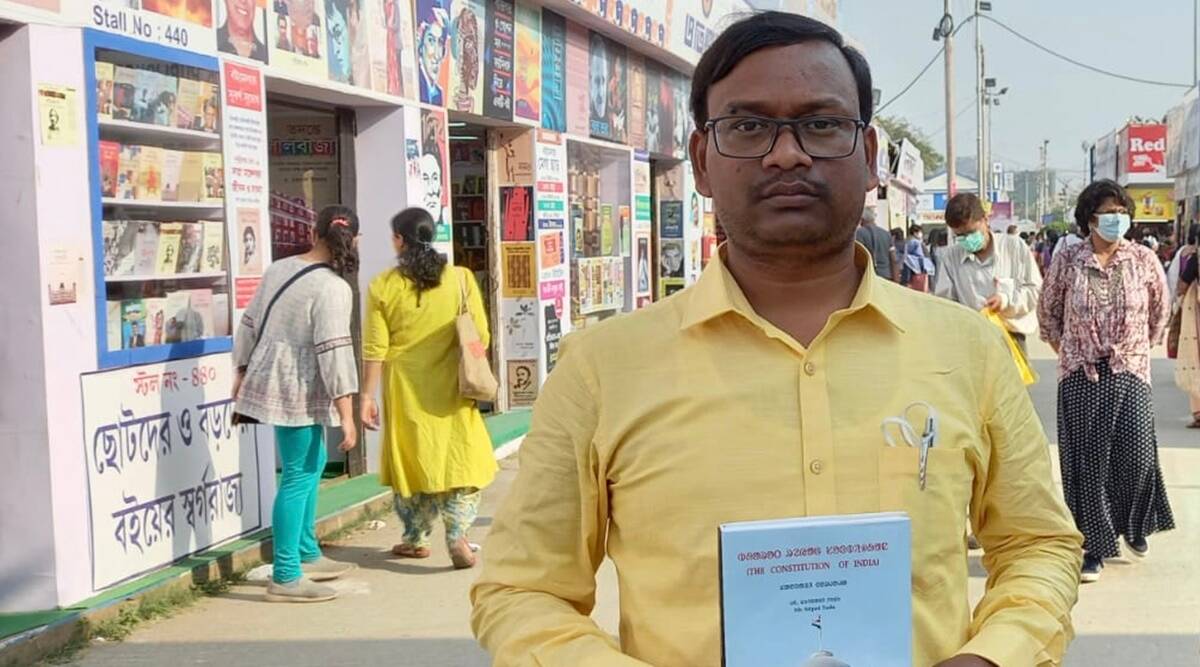

Translating the Constitution of India in Santali had been on

Professor Sripati Tudu’s mind for a few years before he actually got down to

starting the mammoth task: that of translating the longest written constitution

of any country in the world—235 pages—in the Ol Chiki script.

An assistant professor in the Santali language at the

Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University in Purulia, West Bengal, Tudu started this

initiative because he wanted the document to be more accessible and available

for a wider group that may not necessarily be familiar with languages in which

a translation of the Constitution is available. “The nation runs on the basis

of the Constitution. But the community has been historically deprived and so

people in the community need to read it to understand what their rights are,

the provisions and what is written inside,” Tudu told indianexpress.com.

In 2003, the 92nd Constitutional Amendment Act added Santali

to Schedule VIII to the Constitution of India, which lists the official

languages of India, along with the Bodo, Dogri and Maithili languages. This

addition meant that the Indian government was obligated to undertake the

development of the Santali language and to allow students appearing for

school-level examinations and entrance examinations for public service jobs to

use the language.

According to the 2011 Census of India, there are over 70

lakh (seven million) people who speak Santali across the country, and the

community is the third-largest tribe in India, concentrated in seven states in

large numbers, including in West Bengal, Odisha and Jharkhand. But their

geographic distribution is not limited to India—the community is also spread

across Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal.

While the demands for the use of the language had been in

the works for over a decade, the addition of Santali to the Constitution’s

Schedule VIII gave the language and the community an opportunity that had

previously not been available. “At that time, the demand and scope for this

language really increased. It started getting taught in government schools. In

West Bengal, we also got a Santali academy,” said Tudu. In 2005, India’s

Sahitya Akademi started handing out awards every year for outstanding literary

works in Santali, a move that helped preserve and give more visibility to the

community’s literature.

For months before the chips fell into place, Tudu faced

difficulties in finding a publisher for his book. “A large part of publishing

Santali books involves self-publishing, where the author has to put together

funds. There are just five to six publications that publish Santali books and

they have a lot of conditions. They take a huge portion of the earnings, the

copyright belongs to them etc.,” said Tudu.

Sometime in 2019 when Tudu met with Taurean Publications, a

Kolkata-based publisher that had published its first Santali language book only

months prior, he found that it was eager and willing to publish his translation

of the Constitution. “When the Covid-19 lockdown

started (in March 2020), I began the work of translating it in earnest. I asked

around, but the Constitution had never been translated in Santali before. There

were some who had translated parts of it, but it had never been done in its

entirety this way,” Tudu said.

The book was published last year, and is available on Amazon

and on the website of the publisher. Last week, at the Kolkata Book Fair, the

Santali version of the Constitution was also available for purchase at a stall

run by the Paschim Banga Santali Academy.

Vinod Kumar Sandlesh, the joint director of the Central

Translation Bureau, Department of Official Languages under the Union Ministry

of Home Affairs, told indianexpress.com that “any Indian national can translate

the Constitution in their own language”. The department oversees the

implementation of the provisions of the Constitution relating to official

languages and the provisions of the Official Languages Act, 1963. “They have

every right to do so. They do not need permission for translations. The

individual also has the right to generate income by selling their translation

of the Constitution,” said Sandlesh.

Although finding publishers for Santali language books is

hugely difficult, in Tudu’s case, the challenges began only once he started the

translation, because of the complexity of the terminology. The process involved

multiple readings of the Constitution in English and Bengali to understand the

nearest approximation of the terms in Santali. “The words of the Preamble

are so difficult to translate. So many terms didn’t have a Santali word for

them. I finished reading an entire Santali dictionary but I couldn’t find the

right terms,” Tudu recalled.

Tudu points to words like “dual citizenship” for which he

struggled to find a Santali equivalent; these eventually had to be explained in

short phrases, with the original term in English typed next to it. “I couldn’t

really ask others for help because there were very few people who had read the

Constitution and were also fluent in Santali. There are a few Santali

professors of political science whom I spoke with to understand concepts before

translating, but there were times when they did not know the right Santali term

for a word. They were able to explain it to me in Bengali, but they did not

know the specific term for it in Santali,” said Tudu.

Two months ago, 27-year-old Balika Hembram, an MPhil student

at Vidyasagar University in Midnapore, purchased a copy of the Constitution of

India translated in Santali. “There is a lot of demand for the Constitution in

Santali among students in the higher secondary level,” Hembram said. She hopes

to teach political science in schools to Santali students and the translation

is indispensable for aspiring educators like her.

The Constitution of India has special provisions for the

development of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and the

translation has been useful in providing a deeper understanding of laws, powers

and the community’s fundamental rights for readers like Hembram.

Adivasi scholars often point to Article 21 under Schedules V

and VI of the Constitution that set out the rights of tribal peoples to development

in ways that affirm their autonomy and dignity, and are considered by many to

be the foundation of Adivasi rights.

For a community, the Constitution’s availability in Ol Chiki

script is giving a chance to more people to read it for themselves.